Minting errors represent one of the most captivating categories in numismatics. These manufacturing defects not only document the historical craftsmanship of mint operations but are highly sought after due to their rarity.

From doubled die errors during the die-making stage to off-center strikes during the striking process, each error type possesses unique formation mechanisms and identifying characteristics.

In the realm of gold coinage, the stringent quality control applied to precious metal production results in error coins appearing far less frequently than on regular circulation pieces, causing their market values to often multiply several-fold.

This article systematically introduces twelve major minting gold coin error types, providing detailed analysis of their causes, identification points, and collectible value, offering coin enthusiasts a comprehensive reference guide.

Die Multiplication Gold Coin Errors

1. Doubled Die Obverse Errors (DDO)

The formation of Doubled Die Obverse errors stems from the die manufacturing stage, where a hub containing raised design elements transfers the pattern onto blank dies through multiple impressions.

Before 1997, dies required multiple impressions because a single strike wasn’t sufficient to fully transfer design details, and mint workers used alignment guides between impressions to prevent overlapping.

When these alignment guides failed and the hub shifted position during subsequent impressions, the finished die carried duplicate images that would appear on every coin struck from that flawed die.

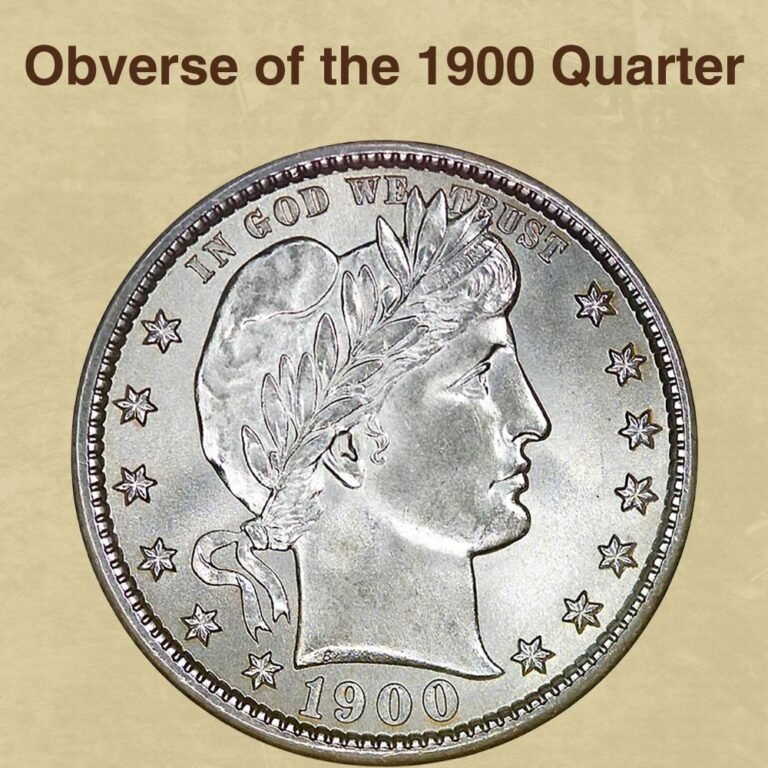

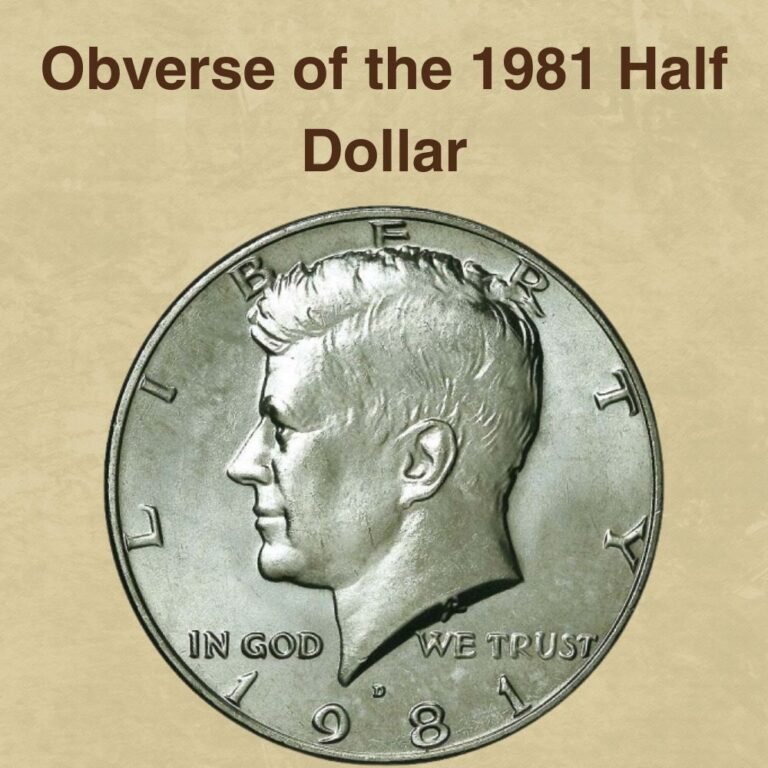

The distinguishing visual characteristic of DDO errors is distinct, raised duplicate images rather than smeared effects, most commonly visible on inscriptions like “LIBERTY” and “IN GOD WE TRUST”. A notable example is the 1862 Indian Princess Gold Dollar DDO FS-101, which displays prominent doubling on the obverse design elements.

While documented DDO errors on gold coins are considerably rarer than on circulating coinage, market values for DDO errors depend heavily on visibility of doubling, historical significance, and preservation quality, with dramatic examples commanding substantial premiums driven by collector demand.

Values vary tremendously—common or subtle varieties may bring modest premiums of several dollars, while rare specimens with pronounced doubling can reach thousands or even exceed six figures at auction depending on grade and desirability. The 1862 Gold Dollar DDO FS-101 variety has an auction record of $3,840 for an MS65 grade specimen sold at Heritage Auctions in February 2022.

2. Doubled Die Reverse Errors (DDR)

A Doubled Die Reverse error, abbreviated as DDR, occurs when the reverse die receives multiple misaligned impressions from the working hub during the die manufacturing process, resulting in duplicated design elements that appear on every coin struck from that defective die.

The root cause lies in the creation of dies, where the mint uses a hub to create coin dies, and if the hub is not perfectly aligned during multiple impressions, the image imparted will be off-center, producing coins with doubled images, letters, numbers, or words.

The formation happens during the hubbing stage, where a misalignment can occur along three orthogonal planes and three orthogonal axes between the first and subsequent hubbing impressions, or sometimes during the course of a single hubbing.

Identifying DDR errors requires magnification and careful examination, as true doubled die coins display both sets of design elements raised from the field with the same height, unlike mechanical doubling, where the secondary impression appears flattened or pressed to the side. The spread is typically strongest toward the rim and weakest toward the center, with characteristic rounded doubling, notched serifs, and clear separation lines visible on affected design elements.

In gold coinage, DDR varieties are considerably rarer than in base metal denominations, though error collectors seek out die cracks and doubled dies in the Indian Head Half Eagle series. Market values for DDR gold coins vary dramatically based on the strength and visibility of the doubling, the coin’s overall grade, and the rarity of the specific variety.

Date Gold Coin Errors

3. Overdate Errors

An overdate error displays two different year dates superimposed on a single coin, creating a distinctive layered appearance where portions of both numerals remain visible.

This phenomenon occurred when mint engravers punched a new date over an existing date on a working die, typically reusing the previous year’s die to address shortages or avoid the labor of fabricating entirely new dies.

For early U.S. gold coins, overdates resulted from intentional die recycling rather than accidental mistakes, as the cost-conscious mint extended die life whenever possible.

The formation process centered on the die preparation stage, where engravers would set untempered dies on their workbenches and use steel number punches plus mallets to stamp new digits over old ones.

A prominent example is the 1806/4 Draped Bust Quarter Eagle, where the “6” was struck over a “4,” with remnants of the underlying “4” visible within and around the “6.” Identifying authentic overdates requires examining the date closely under magnification, as the earlier numeral typically appears thinner and smaller than the replacement digit.

Only 1,136 examples of the 1806/4 quarter eagle were produced, with fewer than 100 specimens thought to exist today in all grades. Market values escalate significantly with grade and the visibility of the overdate feature. A PCGS EF40 example sold for $11,400, while choice AU-58 specimens are considerably rarer, with only 15 certification events listed at that grade or finer by PCGS.

These early gold overdates represent fascinating numismatic artifacts that document the practical realities of early U.S. Mint operations, when die conservation took precedence over creating perfect striking surfaces.

4. Repunched Date Errors (RPD)

A Repunched Date error, commonly abbreviated as RPD, occurs when one or more digits of a date are punched into a working die more than once in slightly different positions, resulting in overlapping or separated images of the same numeral on the finished coin.

Until 1909, each die’s date was placed by hand using a hard steel punch and a hammer when the die was in an annealed or softened state, and the repunching occurred when the date punch was struck multiple times with a mallet.

The formation process was entirely manual during the die preparation stage, where mint technicians positioned a puncheon, a small steel rod with the mirror image of a number on it, and struck it with a hammer to press the image into the die, and if the image wasn’t strong enough or wasn’t positioned correctly, the technician would punch it a second time in a slightly different position.

Identifying RPD errors requires careful examination under magnification, as the secondary impression is usually thinner and smaller than the primary numeral because the raised letter on the punch tapers in vertical cross-section, with the apex being narrower than the base. Some repunched dates are subtle while others are extremely dramatic, with examples ranging from simple doubled digits to quadruple-punched dates showing remnants of four impressions of the same digit.

In gold coinage, RPD varieties are relatively uncommon compared to base metal denominations, though an 1881 Liberty Head Half Eagle with FS-304 RPD designation recently sold for $1,560 in MS-63 grade. The market value of RPD gold coins depends heavily on the visibility and drama of the repunching, the coin’s grade, and the overall scarcity of the variety.

5. Misplaced Date Errors (MPD)

Misplaced Date errors, commonly abbreviated as MPD, occur during the die preparation process when date digits are accidentally punched outside their intended position on the working die.

These errors typically resulted from mint employees testing date punches directly on dies or accidentally dropping date logotypes onto the die surface, causing extra numerals to appear in unusual locations such as the denticles, bust area, or other design elements.

Unlike simple striking errors that affect individual coins, MPDs originate from flawed dies themselves, meaning every coin struck from that defective die displays the identical misplaced digit.

This phenomenon appeared across nearly all denominations produced between 1842 and 1908, with the notable exception of three-cent silver pieces. The era of MPDs ended in 1909 when technological advances enabled dates to be incorporated into the master hub rather than hand-punched into individual working dies.

Among precious metal examples, the 1847 Liberty Head Half Eagle minted in Philadelphia exemplifies this error type from its peak period, with one MS62-graded specimen realizing $34,500 at Heritage Auctions, demonstrating how these historical minting anomalies command significant premiums in today’s numismatic market.

Mintmark Gold Coin Errors

6. Repunched Mintmark Errors (RPM)

Repunched Mintmark varieties emerge when mint technicians manually struck the mintmark punch multiple times into a working die, creating overlapping or offset impressions of the same letter that subsequently appear on every coin produced from that die.

Before 1990, mint marks were manually punched onto working dies from the coin hub, where a technician would align a steel punch bearing the mint mark and strike it with a mallet, and if the first impression was misaligned or weak, a second blow was applied, sometimes at a slightly different angle or position.

The formation stemmed from several mishaps during die preparation, including failure to position the letter punch precisely over a first attempt, a letter punch that bounced and landed lightly on the rebound, or a punch not held vertically which caused it to skip and leave a secondary impression.

Identifying RPM varieties requires magnification to observe the secondary mintmark, which usually appears thinner and smaller than the primary mark because the apex of the raised letter on the punch is narrower than the base, creating a tapered effect in vertical cross-section.

In gold coinage, RPM varieties remain relatively uncommon compared to base metal denominations, with such varieties appearing particularly on Liberty Head Half Eagle issues from the 1840s and 1850s.

Market values for RPM gold coins escalate significantly based on the repunching’s visibility and the specimen’s grade.

A notable example is the 1846-D/D Liberty Head Quarter Eagle, which demonstrates substantial collector demand, with an AU58 example achieving $26,400 at a Stack’s Bowers auction in August 2022, reflecting the premium commanded by well-preserved examples of these scarce Southern branch mint varieties bearing documented die anomalies from the hand-punching era.

Die Defect Gold Coin Errors

7. Die Cracks Errors

Die cracks occur when striking dies fracture under immense minting pressure, creating gaps that allow metal to flow into the crack and form raised lines on finished coins. Dies undergo heat treatment to withstand production stress, but this hardening process makes the steel brittle and prone to cracking, despite subsequent tempering to reduce brittleness.

As dies approach terminal state, crack-like structures appear on coins where planchet material flows into die fractures during stamping, similar to deliberate design features.

Market value depends on crack severity—most minor examples add little premium, while prominent cracks on key varieties can command significant increases, with notable examples ranging from modest amounts to several hundred dollars. Gold coins with die cracks are particularly desirable since errors in precious metal coinage are inherently rare, often selling for two to five times standard values.

The 1848 Liberty Head Quarter Eagle illustrated represents classic early American gold coinage where production demands during the California Gold Rush created conditions conducive to die deterioration, making authenticated examples with visible die cracks sought after by specialized collectors.

Strike Gold Coin Errors

8. Off-Center Strike Errors

An off-center strike occurs when a planchet fails to position properly between the striking dies, resulting in only partial design transfer to the coin’s surface. The blank must be missing some portion of the intended design for it to qualify as an off-center error rather than another strike anomaly. This dramatic error displays visible blank areas on the planchet where lettering, central design elements, or rim denticles are completely absent.

The formation occurs during the striking phase when automated feeding mechanisms misalign the planchet, causing it to fall short or overshoot the striking chamber. Without proper collar restriction, the dies strike whatever portion of the planchet is positioned between them. The severity depends on both the extent of the misfeed and striking pressure, with measurements calculated as the maximum radial distance from the planchet edge to the unstruck crescent, converted to a percentage of standard diameter.

Distinguishing genuine mint errors from post-mint damage requires understanding that authentic errors occur before or during the final strike, while any defect afterward constitutes damage regardless of where it happens. Examining metal flow patterns and field characteristics under magnification reveals whether deformation occurred during striking or from subsequent handling.

For gold coins specifically, off-center strikes are exceptionally rare due to enhanced quality control during precious metal production. Finding even a five percent off-center gold coin proves extraordinarily difficult, while fifty percent examples are nearly impossible.

Indian quarter eagles represent the most frequently encountered off-center gold errors, with three to five percent specimens commanding premium prices. A 1910-P example struck five percent off-center graded MS65 reached over forty-five thousand dollars in 2023.

Dramatically off-center gold pieces, particularly those fifty percent or more displaced, can command prices ten to twenty times their normal value. Collectors should prioritize authenticated pieces from major grading services, as gold coin off-center strikes rank among numismatics’ most desirable striking errors.

9. Strike Through Errors

Strike-through errors occur during the striking phase when a foreign object comes between the die and planchet, preventing proper design transfer.

This obstruction leaves its impression on the coin’s surface, causing weakened details, missing elements, or unusual textures where metal couldn’t flow normally into the die’s recesses. Common obstructions include grease filling die cavities, metal shavings, cloth fragments, staples, or other debris that inadvertently enters the striking chamber.

The error divides into two categories: standard strike-throughs where only the impression remains after the foreign material falls away, and retained strike-throughs where the actual debris stays embedded in the struck coin. Retained varieties are approximately one hundred times rarer because most foreign objects either fall away after striking or remain stuck to the die and continue affecting subsequent coins until worn down.

Gold coins with strike-through errors attract particular collector interest, with prominent examples on gold and silver pieces sometimes reaching thousands of dollars at auction. Value depends primarily on the error’s dramatic appearance and the type of obstruction, with retained strike-throughs typically commanding prices five to ten times higher than impression-only specimens.

However, strike-throughs on inherently rare classic coins may reduce rather than enhance value, as serious collectors of those specific issues typically prefer pristine examples without manufacturing defects.

Planchet Defect Gold Coin Errors

10. Cracked Planchet Errors

A cracked planchet error occurs when the metal blank used to strike a coin develops a visible split or fracture, typically caused by impurities or contaminants trapped within the metal itself. This defect usually happens during the planchet preparation process when improper heating makes the metal brittle, leading it to crack when subjected to the tremendous pressure of the striking operation.

Unlike die cracks that only appear on one side and create raised lines in the design, planchet cracks are actual breaks in the metal that can be visible on both surfaces of the finished coin.

For gold coins specifically, comprehensive pricing data for this particular error type is limited in available auction records, though comparable examples show significant premiums over non-error specimens—for instance, an 1866 Three Cent Nickel with a planchet crack sold for $960 versus the expected $150 for an error-free example in the same grade.

The value premium depends heavily on the coin’s base denomination, overall condition, and the crack’s severity and visual impact on the design.

11. Lamination Errors

Lamination errors form during planchet preparation when foreign materials such as metal dust, slag, debris, grease, oil, or gas become trapped beneath the metal surface as ingots are melted and rolled into strips for coin production.

These impurities create horizontal planes of weakness causing the metal to flake, peel, crack, or separate, with the error developing either before or after striking. Identification requires examining characteristic rough, grainy surfaces at separation points and, for clad coins, verifying reduced weight where layers are missing.

For gold coins, lamination errors typically add forty to one hundred percent premiums over standard values due to their rarity in gold caused by the metal’s purity. Market values range from modest amounts for minor defects to approximately fourteen hundred dollars for substantial laminations on twenty-dollar Double Eagles, with premiums increasing progressively from base metals to silver and then gold coins.

The 1839-D Classic Head Quarter Eagle with reverse lamination graded NGC AU-55 represents a particularly significant case, combining early Dahlonega Mint production from only the facility’s second operational year with a certified planchet error.

Standard 1834 Classic Head Quarter Eagles in AU-55 grade typically sell around fifteen hundred dollars, while Dahlonega examples command higher premiums, suggesting this error specimen likely achieved values substantially exceeding typical pricing for the date and mint combination.

12. Clipped Planchet Errors

Clipped planchets represent one of the most well-known error types, found on coins from colonial era through modern issues, with curved clips being the most common type comprising the majority of all clipped coins.

Clipped planchet errors occur during the blanking process when metal strips are improperly fed into the blanking press that punches circular blanks from sheets of metal. When the strip doesn’t advance properly, subsequent punches overlap previously punched holes creating curved clips, or when punches strike the strip’s leading or trailing edge, they produce straight or ragged clips.

Authentic clipped planchets display the Blakesley Effect, characterized by rim weakness or absence directly opposite the missing portion, occurring because pressure is relieved during the rimming process when the clip area contacts the roller. Additional identification features include stretched designs near the clip where metal flows toward the missing area during striking, and smooth edges at the clip location distinguishing genuine errors from post-mint damage.

Market values for clipped planchets vary dramatically based on clip size and denomination, with small clips on common modern coins worth five to ten dollars while large clips can command two hundred dollars or more. Gold coins with clipped planchet errors command substantially higher premiums than base metal coins with identical errors, with values ranging from modest sums for minor clips to hundreds or thousands of dollars for dramatic examples on rare gold coins.

While specific auction records for gold coin clipped planchets are scarce in available databases, these errors on precious metal coins consistently achieve premiums multiple times higher than their counterparts on lower denominations due to the intersection of precious metal content, inherent rarity, and collector demand for mint errors on gold coinage.

Final Words

Gold coin minting errors represent a remarkable convergence of historical craftsmanship, rarity, and investment value. The stringent quality control applied to precious metal production makes these manufacturing anomalies exceptionally scarce, transforming what might be considered defects into highly coveted collectibles commanding substantial premiums.

Success in this specialized field requires understanding formation mechanisms, mastering identification techniques, and prioritizing professional authentication through major grading services. Whether pursuing dramatic off-center strikes or subtle repunched varieties, collectors should seek specimens where errors enhance rather than diminish overall appeal.

These fascinating artifacts offer both the intrinsic security of gold content and numismatic premiums that remain resilient across market cycles, ensuring their enduring significance in numismatics.

The post 12 Rare Gold Coin Errors List with Pictures (By Year) appeared first on CoinValueChecker.